Originally Written for Internet Economics and Digital Media at Emerson College, taught by Dr. Tylor Orme

Paying for informative media has long been an issue: is the free press a public good that the government should pay for with subsidies, or is it essential that the press be a private entity that is able to report on the government without risking their funds? If so, how are they able to charge for that information that is supposedly essential to everyday life? In general, broadcast news media (like TV or Podcast) and written news/reporting (like newspapers or magazines) both have been built and distributed through shadow pricing, but now there are ethical and sustainability questions that are pushing some informative media towards a subscription model.

Shadow pricing is the method of funding in which, rather than having consumers pay directly for a product, advertisers pay the producer to run their ad, and consumers “pay” by watching those ads. This has traditionally been the main funding used in informative media like broadcast and print media. In broadcast, this works because people are receiving their news on a free cable or free radio provider that they are already expecting to watch commercials on. Print media, on the other hand, have traditionally charged consumers to purchase their print issues because it’s been a physical, excludable good, but publishers have always made most of their money off of their advertised shadow pricing.

Recently though, shadow pricing has begun to fall through, particularly in print media. With the availability of “free”, easily accessible, and more environmentally friendly, information online, print sales have dropped so far that advertisers aren’t willing to pay enough to keep those magazines or newspapers running in print. Magazines and news sites have tried to incorporate shadow pricing into their websites, but click through rates are so low that it’s not enough to support their hard-hitting journalism. As a result of all of this, newly-digital news outlets are left with two options: put out lower quality content that gets more clicks and boosts their advertising revenue (think Buzzfeed), or require people to subscribe to their online media for a direct per month fee (think the New York Times). This is less of an issue with broadcast journalism because it would be odd for a subscription based platform like Hulu or Netflix to create their own news channel that would get chosen over the free cable version.

There are a few ethical issues surrounding this debate between subscription based and shadow priced once-print-now-digital news media. This derives from the type of reporting media publications are able to do in either situation (long tail or short tail), whether or not the integrity of the reporting is compromised by relying on advertising, and whether or not a subscription model is exclusionary.

To begin with, and based on something I already mentioned, print news media that relies on shadow pricing to bring in revenue is often forced into creating more “short tail’ content, as in, content that is widely popular and “clickable”, rather than the hard-hitting, in depth, investigative reporting that might lie in the “long tail”, the portion of the curve that is less popular but, might be considered more essential to public good. This is because shadow pricing relies on people actually engaging with the media where the ads exist, and even though a lot of people care about investigative reporting, it’ll hardly ever reach the number of views as something like a viral clickbait article would. What often happens in this situation, is a news media outlet might have subsections of their company. An example of this is Buzzfeed, which has their clickbait/quiz/pop culture portion of their site that they’re so known for, and they also have their really well-done politics reporting. The viral, “internet friendly” portion of their site funds their reporting, but as a result, their general image and reputation is compromised. Most people know Buzzfeed for the listicles and quizzes. We see some of this in broadcast media, where a newscast has to run a few internet friendly segments to get clicks on their website and/or social media, but by and large they’re still known more for their news reporting than for their viral videos, they don’t lose out on much of their longer tail reporting, and don’t ruin their reputation. However, broadcast news doesn’t often go as in depth, as truly long tail, with their reporting, simply because they don’t have as much time on air as a writer has room on their digital platform.

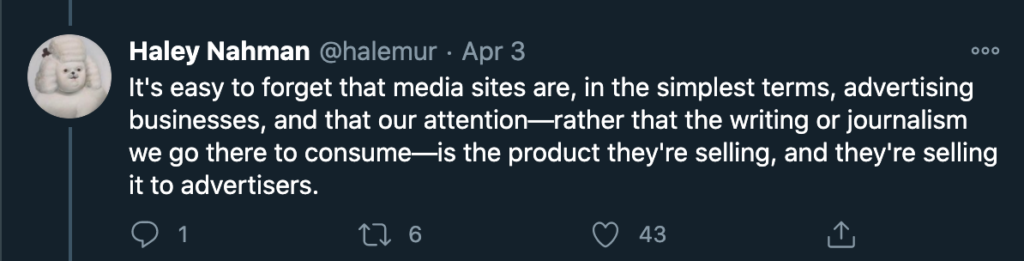

The next issue with shadow pricing is the question of integrity. Just like in the intro I suggested that a government funded news site might not be able to report as freely on issues within the government, for fear of losing revenue, a private online media outlet’s reporting might be compromised by the requirements of its advertisers. A good outlet will find a way to balance this, but it’s still somewhat restrictive. Haley Nahman, a former editor of the online magazine ManRepeller has discussed, on Twitter, her experience of having to turn down good article ideas because it wouldn’t fit with their advertisers (Nahman). The feminist publication Bitch Magazine has attempted to avoid this issue by only using a few local advertisers that fit with their brand ideals, but they’re a non profit so they rely heavily on donations and their higher-than-averge print subscription cost, and even then it’s looking like they’ll become completely digital soon to reduce costs. “Sponcon”, a type of shadow pricing where articles are written as advertisements for a company but are written as if they’re just normal content, is also gaining in popularity. Most magazines and news sites will claim their advertisers have no effect on their content, they do have to label anything that is officially sponsored and paid for by a brand, but it’s hard to imagine a way in which outlets are not restricted on what they do publish based on advertisers they want to make sure to keep, particularly in the massive media outlets that bring in millions of dollars from one brand deal. Again, this isn’t as much of an issue in broadcast media, because people are usually watching their free-with-cable news show that ads are already incorporated into, and the ads aren’t for that one news show and negotiated between the news show and the advertiser, but for the entire channel. And even if an advertiser decides they don’t want to be aired during that news show, there’s still an overarching company funding the news show, and there are a handful of other advertisers who are willing to be aired there.

Finally, and on the other hand of shadow pricing, subscription based news media seems to be exclusive and detrimental to the general public who used to have access to that information. In the case of investigative or political reporting, a subscription model might make those important pieces inaccessible to the people who needed that free access the most. Where a shadow priced outlet or broadcast means everyone can see the breaking and highly important news, a subscription-based outlet is really only accessible to those who can afford it, which might create some information inequality. The New York Times and other major news outlets try to combat this by allowing a certain amount of free articles per month (normally 5), or by offering price discrimination, which makes their subscription cheaper for students, but it can still create an imbalance that negatively effects people who are often already less supported in the media.

While all this might point towards broadcast media being the option that is superior, more accessible, and less affected by issues with funding, it’s important to note again that broadcast media isn’t able to have as long of a tail in its topic coverage than print media is. There’s simply not enough time to go as in depth in a news broadcast, unless you create a dedicated show like 60 Minutes. However, a magazine or news outlet can put out thousands of words in one or multiple articles covering one topic, which then the broadcaster can report on in summary.

There’s no real answer on how to make now-digital “print” media fulfill its accessibility requirements while still getting funded. Maybe it’s the Buzzfeed model, and we have to get over their current reputation issue; maybe it’s something like the New York Times, but just make it free for students or people who qualify. Even more, the diminishing prevalence of true cheap print media makes news, both digital and broadcast, less accessible to those without access to technology. But informative news media is essential to the public’s understanding of truth in the world, and the economics of how it’s funded is something that will need to be solved in order to protect those different industries of free press.

Works Cited

Nahman, Haley. Twitter Thread. April 3, 2020, 12:57PM. https://twitter.com/halemur/status/1246119670735872003