Originally Written for Inequalities: Exploring Causes, Consequences and Interventions at the University of Leeds, taught by Dr. Daniel Edminston

Think, for a moment, about a film student at a prestigious art university. What comes to mind? A black woman from a working class who wants to make films about intergenerational trauma? A non-binary individual who wants to see themselves on screen? A disabled person who’s dealing with the difficulties of a teaching environment not designed for them? Probably not. What normally comes to mind when thinking of the stereotypical film student is the image of a young white man who thinks Pulp Fiction is the greatest movie and aspires to be like Quentin Tarantino.

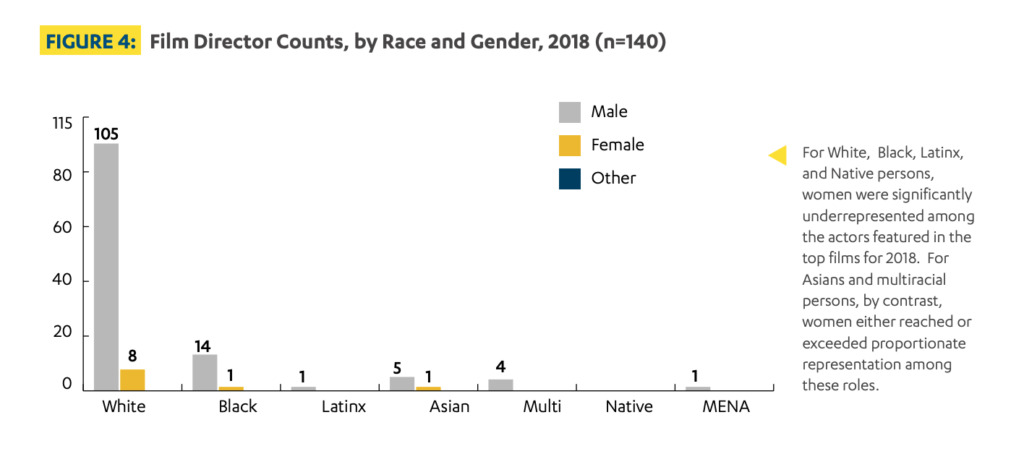

This stereotype has its roots in more than just that annoying kid in your class, however. In 2019, Film Executives in Hollywood were 91% white and 82% male. Only 15% of film directors were people of color and only 15% of film directors were women; 14% of writers were people of color, and only around 17% of writers were women (Hollywood Diversity Report 2020). This, despite people of color making up around 40% of the US population. Diversity on screen has gotten better over the years, according to the same report, largely due to the fact that diverse films have been proven to win awards and make money (Hollywood Diversity Report 2020). Though this data is only in regards to Hollywood, the United States has the largest film industry in the world (Watson 2020) and most of that is based in Hollywood.

(Hollywood Diversity Report 2020)

According to Business Insider, studio executives can make upwards of $5 million/year, directors can make anywhere from $500,000 to $3 million to upwards of $80 million when you include the post-release cuts, and experienced film writers can make about $1 million per script (and more for rewrites) (Siegemund-Broka and Bond 2015).

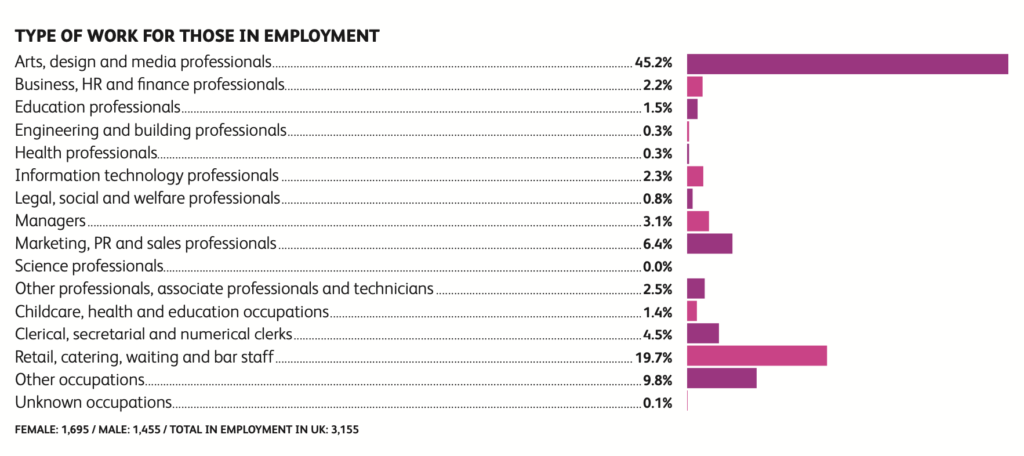

However, according to Prospects, only about 50% of students from “cinematics and photography” backgrounds were working full time in the UK, and only about 1.6% were working overseas, six months after graduation. Of that working percent, only about 45% were working as “arts, design and media professionals” (2018). Even when we look at this broader creative field, not just film or Hollywood specifically, we find that it’s an incredibly risky profession to strive towards. Most people who get film and creative degrees fail and end up in a different profession, or at least one less-glamorous than they’d originally hoped.

Types of work for those in employment

(Prospects 2018).

So how is it, then, that the jobs with some of the most room for fame, fortune, and social mobility go almost exclusively to white men?

One answer may have to do with the social class these high earners come from, and the risk they’re both willing and able to take to make their aspirations come true. Friedman, in analyzing the Great British Class Survey, found “clear lines of variation in the social composition of different elite occupations” (282) and that “even when controlling for important variables such as schooling, education, location, age, and cultural and social capital, the upwardly mobile in our sample have lower incomes than their higher-origin colleagues” (283) (Friedman et al 2015). Though this research was done on the broader population in the United Kingdom, not specifically on the film industry or Hollywood, it serves as an interesting explanation as to why this risky career choice is dominated by white men. With both the pay gap between white individuals and people of color, as well as the pay gap between men and women (Fawcett Society 2017), white men, on average, are of higher-origin in social standing than their female and ethnically diverse counterparts. They’re more likely to make more once they reach high paying careers, and they’re more likely to come from higher class backgrounds. This creates a sort-of safety net or “glass floor”, which protects children from advantaged families from downward mobility (McKnight and Reeves 2017).

White men are not only advantaged enough to afford the prestigious film schools that some independent artists might not be able to, they have that safety net which allows them to take risks—pack up and move to Hollywood to take their shot at work—and they’re likely to make more money once they arrive at their famed careers. Plus, writers and directors are often picked for projects based on how well their previous work did (Vany 2008)—better paying work brings higher budgets and better paying work—meaning this cycle can perpetuate and exclude women and people of color from climbing higher even if they’ve managed to enter the industry.

So too, there’s often an entire system of behavior and etiquette that only those from higher-origins are aware of, which inevitably helps them succeed in entering even higher social spaces. The concept of cultural capital discusses the ways in which people from higher classes are raised with understandings of how to interact in high class social spaces, be it museums, universities, or job interviews, because their families are more likely to have also experienced those things; whereas people from lower classes are more likely to be the first in their family to attend university or go after high paying jobs (Bourdieu 1977). White men have the cultural capital to enter spaces which, historically, only white men have occupied.

These executives, writers, and directors are lauded for their hard work, imagination, and creativity within the industry, but their very existence is based on generations of privilege that helped them get to where they are. And though this post has used the film industry as an example to discuss the ways in risk and attainment can be thought of as representatives for socio-economic standing, the reality is that this exists in almost any industry that can be thought of as risky or difficult to enter. Only those with the background and safety net can even consider going after those risky dreams, because they have their family to fall back on if they don’t make it, whereas people from lower social classes have to be more conservative and limited with their dreams, because if they don’t “make it” they’ll have nothing left.

References:

Bourdieu, Pierre. Outline of a Theory of Practice. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1977.

Friedman, Sam, Daniel Laurison, and Andrew Miles. “Breaking the ‘class’ Ceiling? Social Mobility into Britain’s Elite Occupations.” The Sociological Review 63 (2015): 259-89. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.12283.

Fawcett Society. “Gender Pay Gap by Ethnicity in Britain — Briefing.” News release, March 2017. Fawcett Society. Accessed October 29, 2020. https://www.fawcettsociety.org.uk/gender-pay-by-ethnicity-britain.

Hollywood Diversity Report 2020. Report. Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, UCLA.

McKnight, Abigail, and Richard V. Reeves. “Glass Floors and Slow Growth: A Recipe for Deepening Inequality and Hampering Social Mobility.” British Politics and Policy at LSE. July 25, 2017. Accessed October 29, 2020. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/glass-floors-and-slow-growth/.

Prospects, and AGCAS Education Liaison Task Group. What Do Graduates Do 2018/19. October, 2018.

Siegemund-Broka, Austin, and Paul Bond. “Hollywood Salaries Revealed: From Execs to Extras, Who Makes What.” Business Insider. October 01, 2015. Accessed October 29, 2020. https://www.businessinsider.com/hollywood-salaries-revealed-from-execs-to-extras-who-makes-what-2015-10?r=US&IR=T.

Vany, Arthur De. Hollywood Economics: How Extreme Uncertainty Shapes the Film Industry. London: Routledge, 2008.

Watson, Amy. “Topic: Movie Industry.” Statista. October 26, 2020. Accessed October 29, 2020. https://www.statista.com/topics/964/film/.